Why We Love (and Struggle) the Way We Do

The Science of Attachment and its 3 common misconceptions

Unaddressed attachment wounds will dictate the course of your relationships.

While this is true, very few people are aware of what attachment theory is.

Essentially, the hypothesis is that early caregiver or parent-child dynamics lay the blueprint for the rest of our adult relationships — romantic or otherwise.

Change or healing is possible, but only first through self-awareness.

The theory was developed by psychologist and psychoanalyst, John Bowlby, decades ago.

For the average person, it’s important to note that every relationship you’ve ever had or will have generally follows this theory. The patterns can be subtle, sometimes more pronounced.

When a child is born, “the infant develops feelings of safety and security, and their attachment system becomes deactivated.”

However!

If, the “attachment figure” —( i.e. Mom) fails to adequately respond or provide the love and care for the child, the infant will continue “seek out” a “safe haven.”

And guess what that might mean as we get older…

If safety (or presence) isn’t adequate, you’ll carry that “active need” into adulthood.

As mentioned in this article, tests and scientific studies were conducted on infants to test this hypothesis. The researchers placed infants and their mothers in a room, let the child explore, and then the mother left.

Immediately, they let a stranger walk in to test the child’s response.

They classified the infants into several categories.

Secure: “Secure” infants had a strong capacity to connect well with their mother before and after she left and re-entered the room. ( Though the child may or may not have interacted with the stranger) As you can guess, the same kind of healthy behavior continues into adulthood.

Anxious (Ambivalent): When the mother returned, the anxious child would seem “resistant” after the reunion — despite needing strong contact. In adulthood, this can look like someone who is overly concerned that others won’t reciprocate love and affection. Primarily, because they learned growing up that the parent is unreliable and inconsistent.

Avoidant: In this case, when the mother returned, the avoidant infant did not show distress during separation. The infant interacted with the stranger — by showing avoidance. As I understand it, this can look like avoiding eye contact or pulling away.

Fearful (Disorganized): The article didn’t mention a whole lot about this attachment style, but any infants that didn’t quite fit into a “neat little box” like secure, anxious, or avoidant were categorized this way. But from experience, they’re a hybrid between anxious and avoidant. Their behavior can seem very “clingy” but if their fear of rejection is activated, they can “pull away” like an avoidant.

The more assured the infant is in the availability of their attachment figure in times of stress, the more likely they will interact with others and their environment. Thus attachment, far from interfering with exploration, is viewed as nurturing exploration.

Caregivers who provide a secure base allow infants to become autonomous, inquisitive, and experimental. Children who lack a secure base find their attachment system keeps overriding their attempts to be autonomous and to competently interact with their social environment.

As I’ve seen, the anxious-avoidant dynamic is almost a “magnetic” natural dynamic that almost always happens.

The avoidant’s cold, distant, mysterious behavior is very attractive and alluring to the anxious partner. The avoidant’s behavior triggers their partner’s fear of abandonment.

They will work harder and harder to win the love of the avoidant.

Because the avoidant’s inconsistent, unpredictable behavior reminds them of their unstable childhood, their nervous system is hooked on the chase.

It’s a toxic — albeit familiar emotional roller coaster.

While the anxious partner fears abandonment, the avoidant fears “not being good enough.” Therefore, they will (unironically) avoid conflict or deeper discussions that can lead to rejection — which would “affirm” their “unlovable” nature.

To get around that, they learned very early in childhood that “survival” depended on being hyper-independent, self-absorbed, and aloof.

1. Being secure equals “perfection”

There’s no “perfect” person, relationship, or attachment style. What we need to think of as secure, is more of a “healthy” balance or middle ground between anxiety and avoidance.

No matter how much you work on yourself, grow, heal, or change, you will always predominantly have a certain attachment style.

But social media and the cultural zeitgeist can portray a secure relationship as being without flaws — but relationships are inherently messy.

At the end of the day, secure people are human. They get activated or triggered, whatever you want to call it, in response to “unhealthy” behaviors from a partner.

Like pulling away or leaning in too much. Depending on the situation.

And I forgot to mention that attachment is a spectrum, it’s not a binary system. Think of the green area in this diagram as being secure.

Even those with predominantly secure traits might:

Feel insecure after a major life event like a breakup or job loss.

Have moments of self-doubt or jealousy in a relationship.

Regress to old patterns during high-stress situations.

2. Avoidants don’t want love or relationship.

The avoidant’s aloof behavior — or their reluctance to open up might seem like they don’t want love and connection, but let’s remember, they’re human too.

The basic desire for love and connection is a universal human quality.

If you have an avoidant partner who seems distant or afraid to get close, just remember, they more than likely want to be with you.

It’s just that it’s masked underneath pain, trauma, and avoidance.

They care about you, but at the same time, their primary motivation is to feel safe, not connected.

You have to be aware of that. By reading this article, you can learn to set boundaries and create a strong framework to work on this and potentially improve your connection with them.

Avoidants want love, but they struggle with the idea of relying on someone else. And unfortunately, it’s just the way it is. Which is why it’s crucial to work on yourself and attract more secure partners.

But their internal conflict between desiring connection and protecting their autonomy often creates a push-pull dynamic.

Avoidants do want love; their challenge is navigating the fine line between connection and their deep-seated need for independence.

3. You can only have one attachment style

Attachment styles aren’t strict boxes; they are merely labels or representations of a set of characteristics.

Plus, as we’ve mentioned, attachment exists on a spectrum.

And from my own observation and personal experience, people display a predominant style while exhibiting traits of others in different circumstances.

I primarily identify more closely with anxious tendencies (working on it atm), but if things get too overwhelming, I pull away. Which is more characteristic of avoidance.

You could feel more secure as a person but if you date a moderate or severe avoidant, their inconsistent or erratic behavior can very well trigger your anxious tendencies.

A fearful avoidant might swing between anxious and avoidant behaviors, depending on their emotional state or triggers.

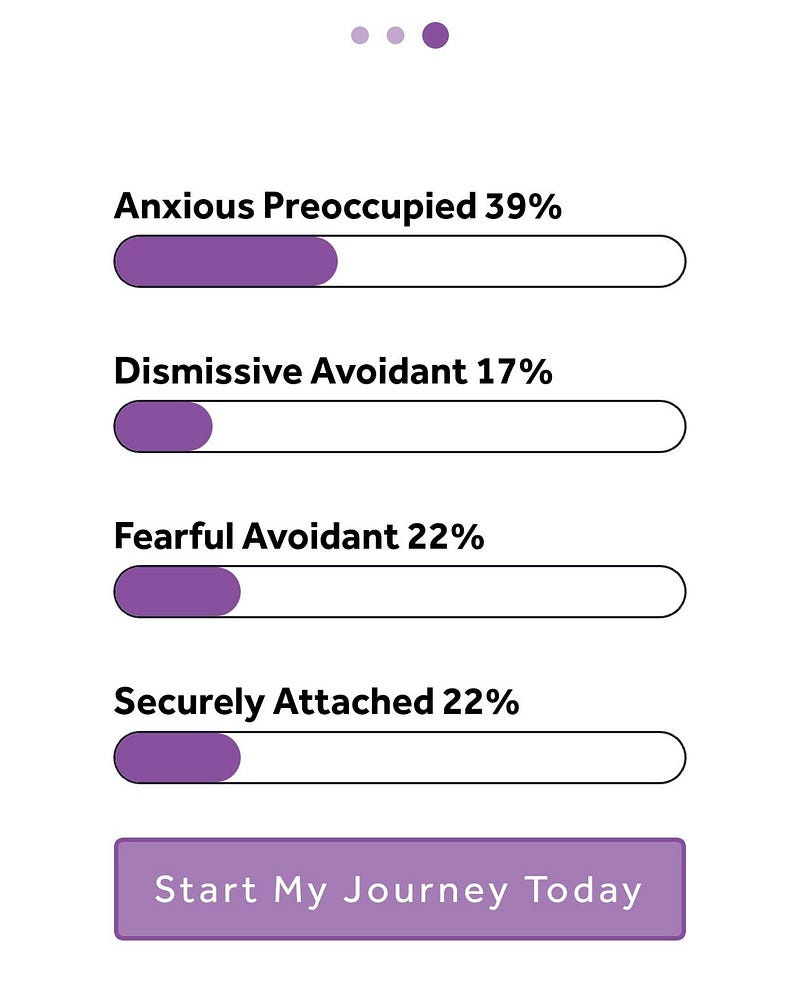

There are a few tests or quizzes you can take for fun that will show you where you might reside on the attachment spectrum.

However, it’s important to keep in mind that these tests aren’t meant to replace therapy or a licensed relationship therapist or counselor.

As an example, here are my “results.”

A few final notes,

Our attachment style is closely tied to our nervous system.

So how we respond to stress and connection (even outside of a relationship) is a strong indicator of how we will respond within a close bond to someone else.

And it’s important to be patient and have grace because these behaviors are deeply ingrained survival mechanisms. It takes time to heal.

Work on letting go and “stabilizing” your nervous system.

Tips for growth and healing:

For anxious partners: Practice self-soothing techniques (like breath work, deep breathing or mindfulness practices), avoid over-analyzing, and focus on building self-worth outside the relationship. Challenge your inner critic and your tendency to over-catastrophize situations.

For avoidants: Work on tolerating emotional intimacy, recognize the benefits of vulnerability and communicate needs openly. I’ve noticed that my tendency to fear conflict perpetuates my avoidant tendencies. In the past, I’ve learned to lean into tension in a few “unavoidable” situations. A lot of that has to do with embracing the “tense” physical sensations in the body — which fundamentally, is what people are trying to avoid.

Enjoy what you just read? Subscribe to my premium newsletter to learn how to overcome excessive thinking and fantasizing, anxiety, and deeper explorations into relationship issues.

Your support not only lets you access more of what you love but also helps me create more amazing content.

Upgrade now and become part of our closer community.